CADA

In Memoriam: Richard R. Whitaker Jr. (1919–2021)

From left: Richard Whitaker, Donlyn Lyndon, Charles Moore, William Turnbull at Sea Ranch, 1991. Photo by Jim Alinder.

Richard R. Whitaker, who played an important role in the art and architecture programs at UIC, passed away in early October 2021. Dick, who first became known nationally through his work with the architecture firm of Moore Lyndon Turnbull Whitaker (MLTW) in the Bay Area in the 1960s, had a long and varied career in architecture, including a substantial period of it at UIC, first as the head of the Department (after 1976, School) of Architecture from 1972 to 1979 and then as Dean of the College of Architecture, Art, and Urban Planning from 1979 to 1991.

Dick was born in Oakland, California, in November 1919 and spent his first years moving with his family from place to place in California. From an early age, he knew that he wanted to become an architect and attend the University of California, Berkeley. First, however, he pursued an undergraduate degree from Fresno State College (now California State University, Fresno), graduating in 1951. Following service in the Korean War, he entered Berkeley in 1957, where he took classes from well-known faculty members, including the industrial designer James Prestini, the architect Joseph Esherick, and, above all, Charles Moore. Moore, who was one of the most charismatic architects and teachers of the postwar decades, became a friend, mentor, and later partner.

Even before he graduated, Dick began practicing architecture, first working as an engineering assistant for the Oakland School District, then in an architectural office in Oakland. In addition, along with several friends, he was able to design and see to completion a church in Squaw Valley in connection with the 1960 winter Olympic games.

Dick received a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Berkeley in 1961. While he had intended to move to India to work on a project with Moore and Ezra Ehrenkrantz funded by the Ford Foundation, the project was canceled at the last minute. Instead, Dick and his wife, Sue, decided to travel to Europe, where they were able to work in a London architectural office and travel around the continent looking at buildings. On his return in 1962, Dick was invited by Moore, who by this time was head of the architecture program at Berkeley, to teach. This he did for the next four years.

During the same year he was invited by Moore to join with him, Donlyn Lyndon, and William Turnbull to form the firm MLTW, initially a fairly loose association of architects working in an office above a railroad station in Berkeley. Their breakthrough project was Sea Ranch, done in collaboration with the landscape architect Lawrence Halprin. This project, heavily informed by rising environmental awareness in the Bay Area, a desire to protect the spectacular oceanfront landscape, and the partners’ interest in the modest frame vernacular buildings of the area, quickly drew international attention and had a major influence on architecture for the next several decades. The years at MLTW were extremely intense and, in addition to Sea Ranch, Dick and his partners turned out numerous projects, including many that won design awards.

In 1965 Dick moved to Washington to become Director of Education for the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the American Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA), as well as a liaison to the National Accrediting Board and the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards. This was a remarkable period in the growth of American architectural education. As the number of architectural programs in the country exploded, Dick was in a prime position to observe and advise as he traveled around the country visiting schools of architecture.

During his years at the AIA, Dick had an opportunity to visit University of Illinois’s program, still located on Navy Pier while the new Circle Campus was under construction. The faculty teaching the art and architecture courses at Navy Pier had been deeply influenced by the educational model of the Bauhaus that had been brought to the United States by former Bauhaus personnel, notably Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, who founded the Institute of Design (ID) in Chicago in 1937. Over time many faculty and students from ID moved to Navy Pier, and its art and architecture program was widely seen as the last incarnation of the Bauhaus. One of its most important elements was the foundation course which was required for all students, whether they intended to be artists or architects. It focused on hands-on exploration of various materials, composition, and use of color.

Dick was extremely enthusiastic about what he had seen. “I went back to Berkeley telling everybody about this wondrous kind of thing I just experienced. You had an art school, and you had a history program, and you had an architecture program. In the first year the art students and the design students and the architecture students were all taking the same courses. And they were all taught by this wonderful group of faculty from all of these different departments. I thought my god, what an incredibly rich thing — a very European model. You had real people who knew what they were talking about and interacting as faculty together. I just thought that was one of the greatest things I had ever seen.”1

Following his time in Washington, Dick moved to the University of Colorado at Boulder in 1967, where he served as associate professor and director of design from 1967 to 1970. There, he spent most of his time trying to revitalize what he considered an out-of-date curriculum. He hired a number of ambitious young faculty members, worked on incorporating environmental considerations into the curriculum, and played a key role in gaining accreditation for the school. He ran afoul of an entrenched senior faculty, however. In the end, he reluctantly decided that his position in the school was untenable and in 1970 accepted a position as associate professor and Eschweiler Chair of Architecture at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee. This was a new program, and once again Dick found himself in an exciting experimental situation. Despite some friction with the dean of the college, he found Milwaukee and the program at the university to be a congenial environment.

But, by chance, at a meeting of the ACSA in 1972 he encountered several faculty members from the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle, including the outgoing dean, Leonard Currie; the incoming dean, Bertram Berenson; and a new faculty member, Felix Candela. They told him that they were looking for a new head of the architecture program and urged him to consider joining the faculty. After initially dismissing the idea he then, with considerable reluctance because he was happily installed in Milwaukee, moved to Chicago to become chair of the architecture department.

When Dick arrived in Chicago, he was chagrined to find that the foundation course and experimental program he witnessed at Navy Pier had been largely dismantled. Although there were curricular elements that remained, artists and architects no longer collaboratively participated in a joint foundation course. Dick was also surprised to see that key faculty, notably Hans Morgenthaler, Alvin Boyarsky, and several other Europeans, had departed. Finally, and perhaps most daunting, he discovered that the financial situation of both the department and university was dire.

Despite these obstacles, Dick played a key role in moving the department away from the more technical and vocational orientation that had characterized the program at Navy Pier and toward one that was more grounded in history, philosophy, and theory and more integrated with the university as a whole. For years he and a number of other faculty members pushed to replace the existing five-year professional Bachelor of Architecture degree, the kind of program seen in many architecture schools, particularly in public universities, with a four-year undergraduate major and a two- and three-year professional graduate program of the kind originally found in elite institutions on the East Coast and increasingly common in the rest of the country. Such programs aimed to give architectural students a broad liberal arts background as well as specific architectural training.

The move was controversial, however, and it was not until after Dick became dean in 1980 that the new program was finally implemented, and it took several additional years before the five-year program was finally phased out. This curriculum initiative paved the way for subsequent heads of the architecture program, notably Thomas Beeby and Stanley Tigerman, to further develop the curriculum and engage more directly with East Coast schools. Faculty members of the time remember Dick fondly as a congenial colleague and Sue as a gracious presence. One of the key events each year was the party the couple gave at their half of a marvelous Prairie Style double house on Ridge Avenue in Evanston.

While he served as head of the school of architecture, Dick was also professionally active at both the local and national levels, traveling constantly to meetings and conferences and arranging to visit schools and look at architecture. Throughout his time in Washington, Boulder, Milwaukee, and Chicago, he also continued to practice on a small scale, sometimes as a sole practitioner and sometimes in collaboration with one or more partners, including with former partners at MLTW. In Chicago he became a partner in the firm of HSW Ltd. along with UIC faculty members George Hinds and Kenneth Schroeder. He also established Whitaker Associates, Architects and Planners with Gigi McCabe and Carol Phelan, both graduates of UIC’s program. Whitaker Associates was responsible, along with his former partners Moore, Lyndon, and Turnbull, for a remarkable house in Winnetka for Carol and her husband, Richard Phelan.

I met Dick when I arrived at the University of Illinois Chicago (then University of Illinois at Chicago Circle) in 1977 when Dick was still head of the School of Architecture. I remember him as a generous presence, a calm mediator in struggles over personnel and curriculum in his own department, and carefully attentive to developments elsewhere in the college. Among other things, Dick was keenly interested in architectural history, something that was not necessarily true of many administrators in schools of architecture, and he was open and accessible. During his tenure the architecture department was renamed the School of Architecture.

While Dick ran the school of architecture the college, then the College of Architecture and Art, merged with the college of Urban Sciences to become the College of Architecture, Art, and Urban Sciences. Following the resignation of Alan Vorhees, the new college’s first dean, Dick was appointed dean. In this role he became involved with the college’s curriculum as a whole and served as an important mentor and mediator in the inevitable turf battles of a relatively new and underfunded college and university. As dean he spent even more time traveling, serving as guest critic and lecturer and participating in a wide range of local and national conferences.

Dick stepped down as dean in 1991 but retained his faculty position. In his remaining years at UIC he taught on the Chicago campus one semester each year and participated in the Rome program during the other semester. Dick believed passionately that architects could benefit from experiencing other places and other ways of doing things, which led him to become the prime force in establishing the Rome program and becoming its director. He resigned from UIC in 1996, returning to the Bay Area which had always been his spiritual home.

In California, Dick lived in Oakland, at Lake Tahoe in a house of his own design, and at Sea Ranch in a splendid house that had been designed by the architect Dimitri Vedensky. He worked actively to maintain Sea Ranch’s integrity until his death. According to his former partner Donlyn Lyndon, “Richard was always dedicated to architecture that serves its inhabitants and nurtures the community, and he invested his talent and that dedication in Sea Ranch for decades, from its inception in Condominium One (1964) until his recent death.” Dick also continued to practice as an architectural consultant, with commissions in California and Chicago. Sue, his companion since his days at Berkeley and always a generous presence, passed away in 2001.

Despite the work he did with MLTW, his involvement with the AIA and ACSA, his presence on the faculty of four prominent schools of architecture, the innumerable conferences in which he participated, the pieces he wrote, and the many awards that he won as a member of various architectural firms, it is surprising how little one can find about his life in recent publications or on the web. I suspect that this is due in great part to Dick’s reluctance to grab the spotlight. He appears to have been, throughout his career, more interested in making things happen and advancing the cause of architecture and architectural education than in taking ownership or pushing his own agenda. Almost everyone that knew Dick pointed to his careful deliberation, his curiosity, his positive attitude toward life and work, and his generosity.

By Robert Bruegmann

Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Art History, Architecture, Urban Planning

Robert Bruegmann is a historian and critic of architecture, landscape, preservation, urban development, and the built environment, and the author of numerous books on architecture, design, and urbanism.

1. Interview with Richard Whitaker by Robert Bruegmann, 1992.

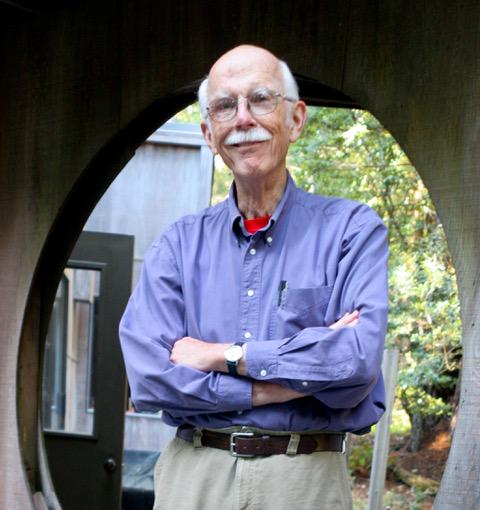

Image: Richard Whitaker at the Vedensky house in Sea Ranch, 2014. Photo by Kevin Keim.