Art & Art History

Tragic and Timeless Today: Contemporary History Painting

Gallery 400

400 South Peoria Street, Chicago, IL 60607

Milet Andrejevic, Roger Brown, Leon Golub, Komar and Melamid, James McGarrell, Nancy Spero, and Mark Tansey

Tragic and Timeless Today: Contemporary History Painting presents seven artists whose works in this exhibition extend and revise history painting, starting with its traditional definition – figurative, didactic, and grand scale. The original practitioners of this noblest of genres, members of 17th – through – 19th-century European art academies, sought subjects in history, mythology, and contemporary life which taught universal, “timeless” truths about human nature; their work aimed at public education rather than private enjoyment. This exhibition featured works by contemporary artists, whose work acknowledges this long-rejected tradition and who sought to modernize it through a variety of styles and strategies. Tragic and Timeless Today offered some of the most talked about artists on the New York and international scenes along with painters enjoying somewhat quieter acclaim.

This exhibition was about a contemporary resurgence of “history painting,” a tradition long thought to have withered after the triumph of the avant-garde in the late 19th century. Defined in the 17th century as the highest category of painting, ranking above the landscape, genre, portraiture, and still life, the “grand style” is best embodied in the gravely dignified pictures of Nicolas Poussin and in works by 18th-century academic masters such as Jacques-Louis David. History painting is figurative and didactic, drawing its subjects from historical chronicles as well as from literature, the Bible and other sacred texts, and classical mythology. Human narratives depicted by means of spare, grandly paced compositions are meant to teach timeless moral truths. Just as Greek tragedy aims at effecting a catharsis that is meant to leave the members of the audience better human beings, so history paintings are intended to uplift the consciousness of the viewers. The seven artists who were presented in this exhibition used methods ranging from the heroic to the parodic, and they each responded to different aspects of the tradition.

In the “postmodern” climate of the late 1980s, the taboos of earlier twentieth-century art were disintegrating. Just as figuration had earlier returned under the guise of photorealism, so too did didactic public art. The artist’s task no longer began with the tabula rasa — wiping the slate of history clean in the quest for more primal, profound forms of expression. But rather, seekers after enduring truth through art once again began to make use of materials lodged in centuries of Western literature and art. Artists who had ignored reigning formalist trends during the 1960s and 70s finally began to gain recognition and an art world context for their work.

The seven artists who were presented in this exhibition used methods ranging from the heroic to the parodic, and they each responded to different aspects of the tradition. Some, including Leon Golub and Nancy Spero, maintain history painting’s original sociological and didactic intent; ultimately, they want to change the way we live and think. Others demonstrate quieter aims; Milet Andrejevic invokes the noble tradition of Poussin in order to demonstrate continuity between past and present – thereby ennobling our day. The huge scale of James McGarrell’s paintings belie their profoundly personal content; he turns majestic Baroque painting conventions upside down in order to express the present psychic instability with sweeping subjectivity.

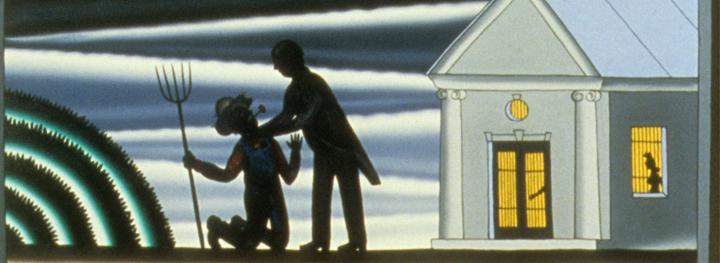

Utilizing the military metaphors that characterize discussions of “advanced art,” Mark Tansey enacts mock battles (The Triumph of the New York School) and “illustrated” allegories of Modernism. The Russian ex-patriot pair Komar and Melamid also use parody to debunk the “heroic” Socialist Realist tradition in which they were trained. Roger Brown’s cartoon-like style cannot mask his serious visual commentary on the omnipresent nuclear threat and America’s weakening position in global politics.

Huge unstretched canvases by Leon Golub, which treat rioting ghetto dwellers or mercenaries, force the audience to confront its own complacency in the face of injustice and cruelty. Nancy Spero invokes the presence of weak and strong women throughout the ages. The cumulative rhythm of her goddesses and tortured women dancing across fragile paper scrolls become a “herstory” – a female alternative to male-dominated “history,” and to the heroic tradition of history painting.

In James McGarrell’s and Milet Andrejevic’s paintings, pastoral visions are inflected with history and echoes of grandeur. McGarrell’s huge multi-paneled work shows the artist creating his own panoramic reality on the expansive scale of heroic painting. Andrejevic ’s smaller pictures dignify New York’s Central Park with classical allusions.

A small, illustrated catalogue accompanied the exhibition.