Art & Art History

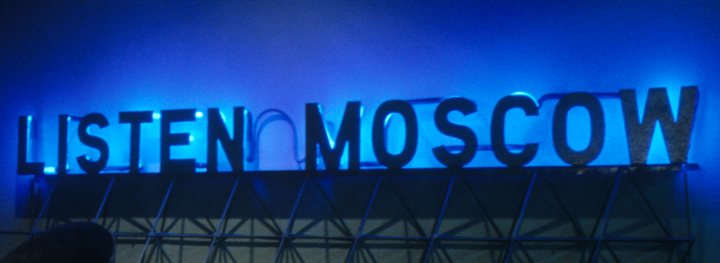

Exhibition 12

Gallery 400

400 South Peoria Street, Chicago, IL 60607

Morris Barazani, Leon Bellin, Phyllis Bramson, Rodney Carswell, Julia Fish, Klindt Houlberg, Martin Hurtig, Linda King, Dennis Kowalski, Susan Sensemann, Tony Tasset, and Charles Wilson

Exhibition 12 is a group exhibition showcasing the work of the Studio Arts Faculty of UIC. Rather than attempting to define a movement or investigate a specific idea, Exhibition 12 demonstrates the diversity of interests, techniques, and approaches that exist among the faculty. Each of the works of art represents and explores the personal, idiosyncratic forms of expression that the individual members of the faculty choose to follow. By uniting the various elements, styles, attitudes, ideologies, and techniques of these artists, it becomes apparent how essential these many vantage points are in creating a successful faculty.

The Studio Arts faculty is the vanguard of the UIC College of Art and Design. It comprises artists who have been recognized on local, national, and international levels. In the two years prior to this exhibition, UIC Studio Arts faculty members exhibited in eighteen states and nine foreign countries. The twelve members participating in the exhibition—Morris Barazani, Leon Bellin, Phyllis Bramson, Rodney Carswell, Julia Fish, Klindt Houlberg, Martin Hurtig, Linda King, Dennis Kowalski, Susan Sensemann, Tony Tasset, and Charles Wilson—follow in the traditions set by former colleagues such as Roland Ginzel, Robert Nickle, Martin Puryear, and Dan Ramirez. Though the diversity of the styles and concerns evident in Exhibition 12 prprohibitshe postulation that some stylistic unity has been achieved in the department, the artists are linked by their commitment to the very highest standards as art professionals and teachers.

As James Yood wrote in his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, “Those institutions of higher education where art is taught in Chicago play no small role in this process. They are the hotbeds of Chicago art, the laboratories where styles and loyalties are forged and reinforced.” Exhibition 12 is an opportunity to appreciate the rich diversity and distinguishing qualities of the artists who are shaping Chicago’s next generation of cultural producers.

Exhibition 12

Introduction by James Yood

Gallery 400, School of Art and Design,

University of Illinois at Chicago, 1989

30 pp., 10 x 9 in., with black-and-white reproductions

This catalogue can be purchased by calling Gallery 400 at 312 996 6114.