Art & Art History

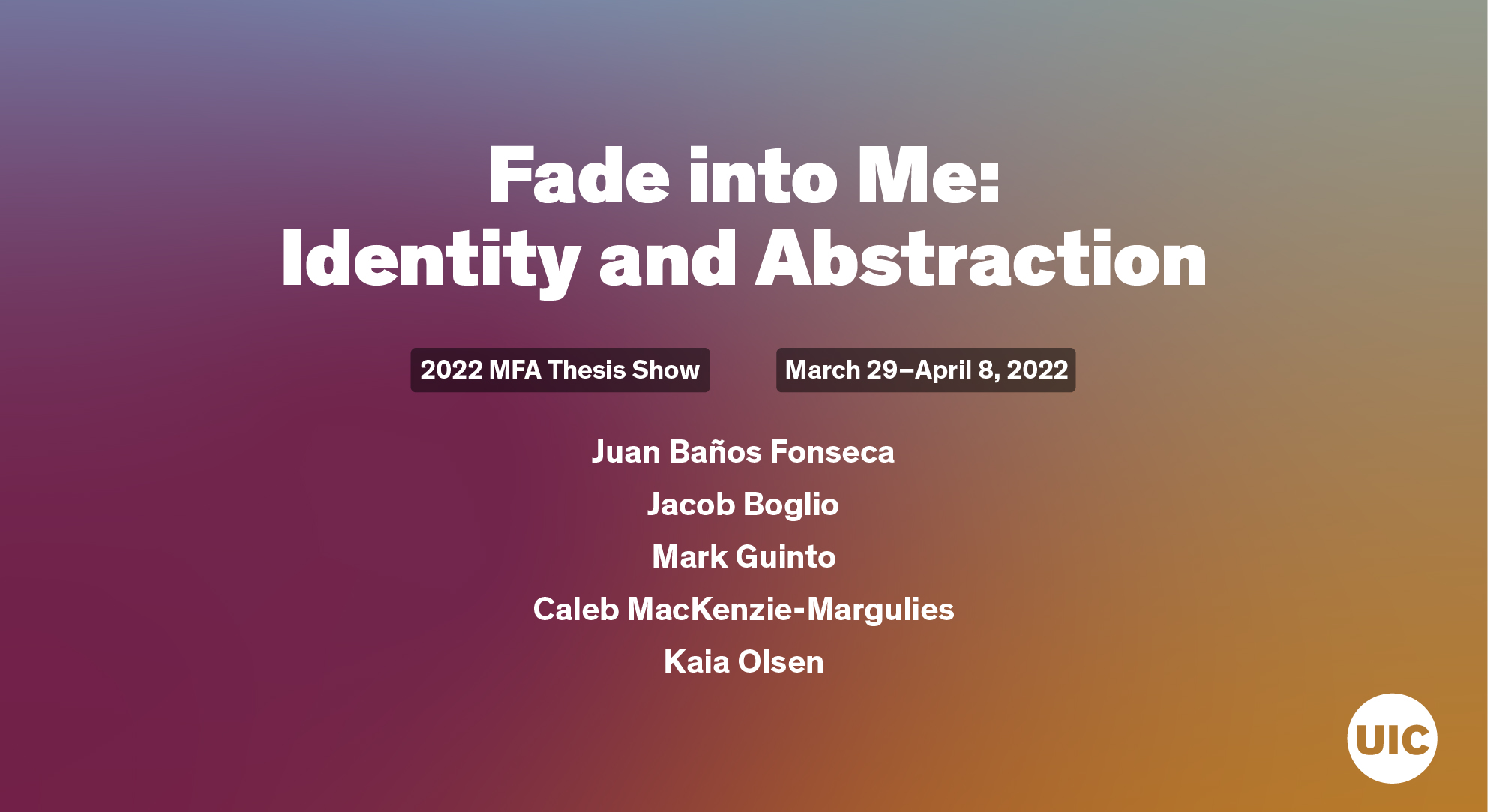

2022 MFA Thesis Show: Fade into Me: Identity and Abstraction

Gallery 400

400 South Peoria Street, Chicago, IL 60607

Caleb MacKenzie-Margulies, Mark Guinto, Jacob Boglio, Juan Baños Arjona and Kaia Olsen

MFA Thesis Talk Friday April 8, 6-7:00pm moderated by Hannah Higgins, Gallery 400 Lecture Room

Closing Reception Friday April 8, 7-9pm Gallery 400, 400 S Peoria St, Chicago IL, 60607

The first of two University of Illinois at Chicago MFA Thesis Exhibitions in Studio Arts, Fade into Me: Identity and Abstraction features Juan Baños Fonseca, Jacob Boglio, Mark Guinto, Caleb MacKenzie-Margulies, and Kaia Olsen.

In Fade into me: Identity and Abstraction, monochromatic brown paintings reference skin color in meditations on race and ethnicity, and the chromatics of rainbow hues painted inside monumental geometric sculptures point to the multiplicity of genders and sexualities. The uniforms of workers stretched into canvases that negotiate the intricacies of class dynamics; prints in photographic and impressed forms abstract punk’s ethos into conceptual acts that point to Jewish cosmographies, and totemic sculptures abstract the human figure into a cacophony of internal voices. Pushing against historical tendencies to represent the self as a physical and political body defined by experiences shared across demographics, Mark Guinto, Kaia Olsen, Jacob Boglio, Caleb MacKenzie-Margulies, and Juan Banos Arjona instead choose abstraction to investigate the materialities of identity. Their works resist easy identification and transparency while simultaneously plumbing the depths of self as an individual in concert with and set against community affiliations, identity politics, and collective ideologies.

Juan Baños Fonseca’s totemic figures stand at the intersection of two worlds. Each is a stand-in for one aspect of the complex interiority of the self in all of its manifestations as it meets external reality. Applying his training in psychoanalysis onto himself, Baños Fonseca parses individual emotions and impulses into singular entities. Each totem is assembled with its own cadre of characteristics pulled from the artist’s study of his own dreams, as well as the images emplaced in him from Catholic iconography. Cobbled from the idiosyncracies of discarded materials, these archetypal representations assemble themselves from the world of late capitalism posed on the edge of collapse. Together, they marvel at the tragedy of lived experience at the intersection of decadence and despair.

Jacob Boglio reclaims discarded materials that signify the working class and abstract them in ways that bring forward their particular materialities and functions. The artist chooses his materials because they have tactical relationships to the bodies of working-class people with the intention of circumventing discard culture and subverting the high prices of traditional art materials like paint. Slept-on bedsheets and uniforms work worn by family members are stretched into canvases. The reflective panels on his father’s construction vest or the blue expanse of his sister’s uniform come to signify “art” when detached from their context and read primarily through form with the effect of transgressing the classed divides of the exhibition space. Spilled coffee, a liquid that fuels labor, and bleach, a liquid that erases the first as well as any other agents, become pigments that carry their significance in daily life into painted space and exhibition space. Bricks, lottery tickets, and other ephemera of working-class life are reconfigured into sculptural installations and artist’s books. Rather than disconnect and decontextualize, Boglio’s working-class abstraction reveals the economy of things that construct working life and ethos, aspects that cannot be represented but only described materially.

Mark Guinto makes paintings that show the limitations of the act of representing as a mode of artmaking as well as the limitations of a politics of representation in hegemonic culture. Drawing from his personal, familial, and cultural experiences, Guinto moves everyday objects from his Filipino-American household into meditations on the residue of colonialism that continues to structure life. Across three walls of the gallery space, Guinto arranges his paintings as an altarpiece. On one side, the painted bodies of a living and dead fly flank the tool of its demise: a fly swatter. Guinto recuperates the fly as kin through its ability to evade and persist. In another series of paintings tenderly copy recipes from post-it notes to translate hastily scribbled attempts to connect with home into lasting documents. Joined by paintings of Timberland boots and a bitter melon, a staple of Filipino cuisine, Guinto speaks to group belonging as well as cultural dexterity.

Caleb MacKenzie-Margulies’s quiet studies of everyday life bridge the distance between the conceptual frameworks of photography and the importance of paper within Jewish material culture. I was born tomorrow is a large spill of photographic, inkjet paper that swirls in voluminous curves in a pile. Its paradoxical title challenges the ways in which time, as experienced by humans, presents itself as a sequenced series of events vis-a-vis photography. The traditional photograph captures these events and transforms them into documents. MacKenzie-Margulies’s is a practice that applies the medium’s methods to frame moments in everyday life. In this case, photographic paper is imprinted through cutting and its real-time relationship with the ever-changing light in the space. Growing up in a Jewish community, in which the written word on paper is of supreme ritual importance, MacKenzie-Margulies is preoccupied with paper as both a vessel and an excess. This photographic paper, originally destined for discard, is transformed into a consecrated material that presents itself to the viewer for our aesthetic and spiritual consideration. Where photography tethers the world to the past by making a document out of the moment in which the photograph was taken, MacKenzie-Margulies’s cameraless photography insists on the presentness of the now, in the place, at the moment in which it is directly experienced. In the process of attenuating us to the experience of the now, he also shifts the temporal landscape of daily life into a consideration of the cosmic.

Kaia Olsen translates a background in dance, choreography, and moving image production into sculptures that exist in states of tenuous balance. By pushing the limitations of material to their maximum capacity, Olsen connotes spaces of fluidity and physical embodiment in the process of a constant state of becoming. In Immergence/Transportal, we witness the process of a heptagon—a seven-side geometric shape — coming into and out of being, in perpetual transition — as a series of dawnings. The shape rises from the ground and, in making more of itself known, becomes a temporal passageway that one can enter, appearing in dualistic states of emergence or diminishment depending on the direction the sculpture is approached. Encountered from the side of its full manifestation, the viewer is presented with the vivid chromatics of the rainbow and invitation to transgress the passageway. From within this portal space, color offers a kaleidoscope of potentiality. From its diminished, waning, side, the viewer is presented with desaturated hues that intentionally suppress their vibrancy. For Olsen, this tension between vibrancy and fullness, desaturation, and diminishment speaks to what he describes as “mode-switching”: the situational need to camouflage one’s identity within spaces of non-acceptance.